Tracey Taylor is a writer, editor and media entrepreneur. In 2009, she co-founded local news site Berkeleyside in Berkeley, California, and in 2020 she was a co-founder of nonprofit organization Cityside, whose mission is to help solve the local news crisis by bringing civic-minded journalism to more communities.

As an independent writer, Tracey’s work has appeared in The New York Times, the Financial Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and a range of magazines. Her articles cover a broad range of subjects, including business, food, homes and architecture, as well as profiles and interviews.

Tracey has written about real estate for Redfin, the San Francisco Chronicle and, independently, on Home Girl. Tracey was editor of Campaign Magazine and Media & Marketing Europe Magazine. She is also the editor of two books: Posters of the Century (Profile Books, 1999) and Finding An Angel Investor (The Planning Shop, 2007).

See Tracey’s full professional credentials on LinkedIn. Contact her by email.

Note: This website stopped being updated in 2007.

———————————————————————————————————-

IN CALIFORNIA, A MID-CENTURY HOUSE IN THE REDWOODS, New York Times

The home’s open plan living space. Photo: Joe Fletcher.

“It sounds very Californian, but this home found us,” said Kim Todd, explaining why she and her husband, Andrew, left a 5,000-square-foot house with a pool and a large landscaped garden in Marin County for a home one-fifth the size, with a single bedroom and a wealth of deferred maintenance.

The couple, who run diPietro Todd, a chain of hair salons in the San Francisco Bay Area, first saw the crescent-shaped house nestled in a canyon of redwood trees here about four years ago, and almost immediately made the decision to move.

“We fell in love as soon as we saw the house and its surroundings,” Ms. Todd, 55, said. “Our work life is so public. It’s really quiet here, and the owls fly by at night.”

She and Mr. Todd, 49, had two children who were nearly grown — Luke is now 17, and Sophie is 21 — and they knew they were approaching the time when they would have to think about downsizing, since they were “soon going to be empty nesters,” she said.

But the architecture was a big part of the appeal. The house was built in 1958 by Daniel J. Liebermann, an architect who had apprenticed with Frank Lloyd Wright, and he was just 28 when he designed it for himself and his wife. Like most of Mr. Liebermann’s homes, it is constructed on a radial frame, with curving exterior walls.

John Lovell, a friend of Mr. Todd’s who is a designer and had studied Mr. Liebermann’s work, showed him the listing when the house came on the market and urged him to take a look. Mr. Todd then passed the listing along to another friend, Wanda Liebermann, an architect who had helped design several of his salons, without realizing she was Mr. Liebermann’s daughter. “That’s the house I grew up in,” she told him.

Mr. Liebermann had sold the house in 1966, but he was living nearby — and still practicing architecture at 80 — and both he and Ms. Liebermann advised the Todds during the early stages of the renovation, although the lion’s share of the remodel was overseen by designer Vivian Dwyer.

But Mr. Todd also spent many hours alone on the property, ruminating about how to proceed. “I would stare at every angle and reconfigure the space in my mind,” he said of the house, which they bought in 2006 for $1,125,000. “In the end, it was clear the original design was best. We chose to edit and make the home more luxurious.”

That meant leaving the interior layout basically as it was, with one important exception: the three cramped bedrooms and two bathrooms in the sleeping area were replaced with a single master bedroom and bathroom, and a walk-in closet handcrafted in wood by a boat builder. (The couple’s son sleeps in an adjacent guest house; their daughter had already left home by the time they moved in a year ago.)

It also meant upgrading the house’s 19 skylights, putting in a new kitchen and refurbishing the radiant heating system. New lighting was installed throughout the house; the wood rafters and the ceiling were wire-brushed and waxed; the concrete floors were restained and polished; and the exposed brick walls were coated with plaster to create a more modern look.

Not surprisingly, the remodeling budget spiraled. “We started with the idea of spending $350 a square foot,” Mr. Todd said. “We ended up spending at least 25 percent more than that — at some point I stopped counting. I just knew we had only one chance to do it right.”

Living in a 1,100-square-foot house has had its challenges. The couple had to get rid of many of their possessions, including most of Mr. Todd’s collection of midcentury modern furniture. “I had to put so much in storage,” he said. “I brought my Mies van der Rohe daybed here, and it was too big, too square.”

Ms. Todd, however, is content to be a minimalist. “This home represents the next chapter for us as a couple,” she said. “It’s our rite of passage.”

—

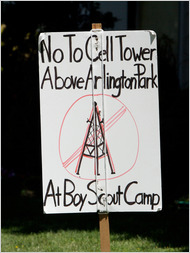

OPPONENTS OF CELLPHONE TOWERS TRY A CHANGE IN TACK, New York Times

Parker Douglas, left, and Eric Burnstein heading to the Camp Herms Boy Scout Camp above Arlington Park in El Cerrito. Photos: Thor Swift for the New York Times.

Last summer, it all seemed so simple. The cellular telephone company T-Mobile approached the Mount Diablo Silverado CouncilBoy Scouts of America to see if it would allow construction of a cellphone tower at Camp Herms, the group’s 23-acre hillside property above Arlington Park in the El Cerrito hills.

The company’s offer included a payment of $2,200 a month for 30 years, money the scout group said would help finance remodeling work at the camp and allow it to create additional programs. The scout council accepted the offer.

What it did not anticipate was the reaction from its members and camp neighbors.

Seven hundred people signed a petition protesting the proposed tower, 250 letters were sent to the scout organization, at least one scout master threatened to move his troop, and a local childcare center and the Sierra Clubadded their names to an orchestrated campaign against the tower. At the center of their opposition are concerns over health risks, particularly for children.

“We were stunned by the response,” said Valerie Ridgers, Mount Diablo Silverado Council’s assistant scout executive. “The tower would look like a tree, and there are no health hazards. The last thing we would ever do is put something up that would harm our scouts.”

The project has been put on hold while T-Mobile does a review, though the company will not say whether this is a result of the protests.

A sense of déjà vu is palpable. Community resistance to cell sites has been common since the mid-1990s, when the first big wave of cellphone tower construction began. In San Francisco, residents are organizing against proposed T-Mobile wireless facilities in at least six neighborhoods: the Sunset, Outer Sunset, the Mission, Miraloma Park, North of Panhandle and Presidio Heights.

In February, the Walnut Creek School District rejected a lease agreement with Clearwire to install a 37-foot wireless broadband Internet antenna at the Walnut Heights Elementary School.

But if the fights are familiar, the context has changed. The question surrounding the protest over the El Cerrito tower and other proposed locations for antennas is: How much coverage is enough? How many camouflaged antenna-trees must be introduced into the landscape to keep all those iPhone apps humming?

The 1996 Telecommunications Act prevents state and local governments from considering health concerns in locating wireless facilities. So the battles are often fought over aesthetics and need.

The growing popularity of smart phones, in particular, is driving demand for more cell sites. Sales of mobile phones stood at 1.2 billion worldwide in 2009, according to figures from Gartner, an information technology research and advisory company, and sales of smart phones rose to 172.4 million in 2009, up 24 percent from 2008.

AT&T says wireless data traffic on its network has grown more than 5,000 percent over the past three years. It says its wireline and wireless investment in California will total $18 billion to $19 billion this year, up 5 percent to 10 percent over 2009, with the addition of at least 200 new cell sites and upgrading about 500 additional sites.

Sprint says the Bay Area is one of its top 10 markets in terms of subscriber demand. Tower Source of Colorado Springs, which maintains an extensive database of cellphone tower sites, calculates there are 2,925 sites in the greater Bay Area, each with multiple carriers.

Nationwide, Tower Source said, demand for sites is increasing at about 13 percent annually.

The San Francisco Neighborhood Antenna Free Union estimates there are upwards of 500 locations and more than 2,500 individual antennas serving San Francisco, not including antennas on light and utility poles in the city’s public rights-of-way, or unlicensed WiFi hotspots in homes, coffee shop and libraries.

This is still not proving to be enough in some parts of the city. To address complaints of patchy iPhone signals, AT&T last month introduced Micro-Cells, miniature towers for inside offices or living rooms, which cost $150.

But as the infrastructure needs grow, opposition is becoming more vocal. In El Cerrito, a group calling itself Arlington Park Against Cell Tower has conducted its own research, which it says proves that local mobile phone signal strength is more than adequate. It suggests T-Mobile does not need the tower to improve coverage because it has a tower a half-mile away at Moeser Lane and Arlington Drive, and says a tower would lower values of nearby properties.

And despite assurances that there is no scientific basis for health worries — the Federal Communications Commissionsays there is no risk from the radio frequency radiation emitted from cell sites — worries persist.

Scott Houser, who leads El Cerrito Scout Troop 104, said that if the cell tower was erected, he would push to move his troop.

“We have this pristine gem in the city in the great outdoors, and I am fearful of the health hazards of a cell tower,” Mr. Houser said.

Nancy Kelleher runs Hug A Bug Pre-School, which is a few hundred feet from where the tower would stand. “There are no guarantees this is safe,” Ms. Kelleher said, “and it’s always after the fact that we find out there are health hazards in cases like this.”

“Child care is a competitive field,” she added. “I might have to relocate.”

Last month, Mayor Gavin Newsom of San Francisco signed a Board of Supervisors resolution calling on the federal Environmental Protection Agency to study the health effects of wireless facilities and requesting the repeal of the limitations that prevent health concerns being considered in cell site siting cases.

Mr. Newsom also supports a bill written by State Senator Mark Leno, Democrat of San Francisco, that would make San Francisco the first city in the country to require that cellphone retailers label their devices with the level of radiation they emit.

But impeding the expansion of the wireless network is a tall order. Roger Entner, an analyst at Nielsen Mobile, said that there were plenty of cases where municipalities had said no to a proposed cell site, but that “every single time, the municipality zoning board blinked and settled.”

Nonetheless, Doug Loranger, co-founder of the Coalition for Local Oversight of Utility Technologies, a nationwide organization working to change federal policy on cell towers and other wireless facilities, said he believed that legislation was tilting in favor of local governments.

Mr. Loranger cited the example of John Avalos, a San Francisco supervisor who is preparing legislation to institute a new permitting process for antennas proposed in public rights of way. He also mentioned the city of Glendale in suburban Los Angeles.

“After an 18-month moratorium on new cell sites that will end this June,” Mr. Loranger said, “Glendale will have adopted one of the most stringent celltower-siting ordinances in the state of California.” The ordinance will increase the city’s oversight of the placement of antennae; cellular equipment proposed for residential areas will face a more intense review process; and carriers may need to prove why the equipment is needed.

In El Cerrito, which, according to the city’s Planning Department, currently has 12 cellphone towers, the debate over another one being put up in Camp Herms is in limbo.

On March 30, T-Mobile informed the city that it was putting its application on hold.

“We want to further evaluate our network in El Cerrito,” said Rod De La Rosa, senior external affairs manager at the company.

Not every El Cerrito resident opposes the tower. Tracy Sichterman, a real estate agent who lives in the Arlington Park neighborhood, said: “I believe the debate about the need for cellphone coverage ended when consumer demand put a cellphone, or P.D.A., in nearly every hand including those of many of our children. Parks and open areas away from homes may make good location candidates for new towers.”

Ms. Sichterman said the effect on home values related to visual impact.

“Real estate values are clearly affected when an electrical or cell tower looms over a property’s backyard,” she said, “but this impact quickly diminishes when the tower is distant.”

On the other hand, Ms. Sichterman has started to see “poor cellphone reception” appear as a property defect in real-estate disclosure statements. “Some buyers, particularly those who work remotely, consider this to be a material concern when purchasing a home,” she said.

—

NONPROFITS ADD MENTORING TO MONEY TO KEEP MINORITIES IN COLLEGE, New York Times

Photo by Heidi Schumann/New York Times.

As college admissions season draws to a close, the spotlight has been on students’ getting a foot in the door. Less attention is paid to how many of today’s high school seniors will emerge a few years down the line with diplomas in hand, and what might cause them to veer off track.

It is much tougher to stay the course in college if you are the first in your family to enroll in college, if you have rarely strayed far from home and if your life is still affected by family problems, be it a jobless parent or an addicted sibling.

At a national level, one student in two enrolling in college earns a degree within six years. In the Bay Area’s most challenged communities, the ratio is far worse.

The problem is most acute among young black and Latino men. According to data gathered by the Oakland Unified School District, only 8 percent of black teenagers entering ninth grade will get a bachelor’s degree.Only 34 percent of black male students, and 44 percent of Latino male students who entered the combined University of Californiaand California State University system in 2001 had graduated six years later. The rate for white men was 62 percent.

That statistic, graduation rates, is in the cross hairs of theEast Bay College Fund. It is perhaps the most visible of a small but growing number of Bay Area nonprofits that are beginning to make inroads in steering young, at-risk students to college, and also helping them through it. The fund’s method is to supplement financial aid with a carefully administered program of mentoring, peer-to-peer guidance and life-skills training.

Experts in education say the program may provide a model for bridging the college completion gap.

Take the case of Jameil Butler. His college aspirations were almost destroyed, despite his talent as a football player, when, in 2003, he took a bullet in the stomach outside a Sacramento nightclub. Then 17 and a football star at Oakland Tech, Mr. Butler had been assured by his coach that he was in line to receive an athletic scholarship. The injury eliminated that possibility.

After seeing a presentation by the East Bay College Fund at his high school, Mr. Butler put his future in the hands of the organizations that provide financial aid to underprivileged students.

Mr. Butler is now about to graduate from Fresno State, and he said he owed his success to being selected by a nonprofit that not only makes money available, but is also committed to assisting its scholars through graduation.

When Mr. Butler’s grades slipped 18 months ago, his East Bay fund mentor was there to help. “I didn’t hold up my side of the bargain for a while,” Mr. Butler said, “but they continued to be in my corner.”

The majority of educational charities have traditionally concentrated on the front end of the process. Government policy has also tended to concentrate on access, and has only recently turned its attention to completion, said David L. Kirp, a professor at the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

“We need more strategies to keep kids in school,” Dr. Kirp said. “The financial crunch has led to higher tuition fees, and cuts in courses, which means some students are facing a more expensive, longer term at college.”

Seeing the horizon stretching out indefinitely can discourage students who are already feeling overwhelmed.

The East Bay fund’s program, which awards individual grants of $16,000 spread across four years, is founded on graduation targets: it aims to have 75 percent of its scholars graduate within six years. Since its start seven years ago, the fund is on track to meet that goal. Twenty-nine of its sponsored students are on track to earn diplomas by the end of this academic year.

Having a mentor’s support through college was crucial for Brittany Chambers. Now a senior anthropology major at Berkeley, Ms. Chambers became a mother while attending Excel College Preparatory High School in Oakland. Despite the obstacles, she decided to try for college. Now she hopes to earn a masters’ degree in public health.

Her mentor, Patty Gates, a lawyer who volunteers for the East Bay fund, helps her prepare for exams, takes her to lunch once a month and is on call to talk. “I call her with personal problems, Ms. Chambers said. “She’s always there.” When the father of Ms. Chamber’s now 5-year-old daughter was murdered, the fund provided support.

Andy Fremder, a co-founder of the fund, said the organization concentrated on Oakland, where 70 percent of high school students are black or Hispanic, groups that are underrepresented on college campuses.

“Oakland can seem like a third-world country to some people,” Mr. Fremder said. “Many of these high school kids live under so much duress that a college education seems like a fantasy.”

Mr. Fremder and his team visit most Oakland high schools each year to talk to seniors about the fund.

In mid-January Mr. Fremder was at Life Academy High School of Health and Bioscience, where about 15 students turned up at a threadbare auditorium to hear him speak. Mr. Fremder opened with a question: “How many of you are interested in getting a $16,000 college fund?” Having secured their attention, he explained that beneficiaries must have a B to B+ average and documented financial need.

They must also be able to demonstrate that they have overcome obstacles and are capable of seeking help. “We want to know your story; we want to know you,” Mr. Fremder said.

Helping Mr. Fremder with the presentation was Sam Becerra, 24, a Latino who grew up in East Oakland. An East Bay fund scholar who graduated from Pomona College in 2008, Mr. Becerra now works in the financial services industry in San Francisco.

Dressed smartly, Mr. Beccera took each question in stride, admitting he had been so nervous on his first day at Pomona that he threw up, but went on to have four enjoyable years.

The East Bay fund is modeled on the Meritus College Fund, a San Francisco group that has awarded 300 scholarships since it was set up in 1996. Its founder, Dr. Henry Safrit, said that when the fund noticed a drop in the number of black men applying for grants it decided to take action.

“These are the kids at highest risk,” Dr. Safrit said. “They drop out of school, never work, are killed. It’s a waste of humanity.”

The fund revised its application requirements to include C grades in certain circumstances, and started a pilot program at two San Francisco high schools, where it monitors and supports every black male student. Erik Moore, a bond trader with Banc of America Securities in San Francisco, volunteers for the East Bay fund. Many of the young men , Mr. Moore said, need affection. “These are macho guys,” he said. “Sometimes you just want to hug them.”

Mr. Moore also makes a point of showing his charges what is possible. He takes them to where he works so they can experience the excitement of the trading floor. He also takes them to fund-raisers in stately homes on the Peninsula.

Mr. Moore, who is black, is in a good position to demonstrate to young black men what can be achieved. He grew up in Richmond and said it was through the encouragement of a next-door neighbor who became his mentor that he went on to graduate from Dartmouth College and get an M.B.A. at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth.

“A lot of the kids want to be Michael Jordan,” Mr. Moore said. “I show them that suits can make more money than athletes.”

The college completion model is getting noticed. In 2008, after many years of channeling its energies toward a diverse number of causes, the Berkeley Community Fund opted to pattern itself on the East Bay fund program and offer four-year scholarships and mentoring to students at Berkeley High School. Donors can choose to support an individual student.

“After we retooled,” said Jessica Pers, board president of the community fund, “we doubled our donations in 2009 over 2008.”

—

ORGANIC OR AUTHENTIC: THE SAUL’S DELI DEBATE, New York Times

What’s not to like about Berkeley’s favorite deli? Why all the kvetching?

In many ways Saul’s Restaurant and Delicatessen in Berkeley — just a few doors down the street from Chez Panisse, the grande dame of the slow-food movement in the Bay Area — is the quintessential farm-to-table restaurant. It features local food, organic produce and a seasonal menu.

So why the consistent grumbling from perhaps one customer in five? Nostalgia, said Peter Levitt, the co-owner and chef who is a Chez Panisse alumnus. “We have so many culinary memories under one roof,” he said.

Which is a nice way of saying that some people prefer pastrami made the old-fashioned way — industrially — and feel that anyone who doesn’t approve of the high-fructose corn syrup in Dr. Brown’s cream soda should just suck it up and adjust.

If there’s one dining experience above others which is pregnant with expectations, it’s the Jewish deli. The pastrami sandwich had better be so large you can barely get your teeth into it. The blintzes had better taste like the ones your grandmother made.

The problem is that the deli menu many people regard as authentic, and which reached its heyday in the 1950s, is rooted in the industrial food system. Those towering pastrami sandwiches are typically created with factory-produced meat. The rye bread? Pasty and processed.

Ever since Mr. Levitt and his partner, Karen Adelman, took over Saul’s in 1995, they have tried to make the restaurant’s voluminous menu more sustainable, as they describe on the deli’s blog.

In 1998, Acme bread (founded in Berkeley) replaced the spongy white rye the deli had shipped in from New York. It is now broadly appreciated. They source their fish from Monterey Fish Company and their beef from Marin Sun Farms.

A year ago, they did away with Dr. Brown’s sodas, both because of the food miles they incurred and the high-fructose corn syrup on the label. The change proved to be the last straw for some die-hard deli fans.

“There were those who said if you don’t have Dr Brown’s, you’re not a Jewish deli,” Mr. Levitt said. “People forget that the original Jewish sodas were handmade and sold off the back of street carts.”

The house-made celery, cream and black cherry artisanal sodas, which took the place of Dr. Brown’s, now have their own loyal following.

Worried about what would happen if he went forward with more changes, Mr. Levitt called for a “referendum on the deli menu.” The event, which was set for Tuesday at the deli, will now be held at a bigger venue (the Jewish Community Center of the East Bay) to accommodate the more than 175 people who are paying $10 each to attend. It promises to explore questions like these: “What taste memories and flavors of the deli have been provided by an industrial food system? How can we look at our nostalgia and expectations critically?”

In fact, most customers appreciate the changes. Their grass-fed corned beef sandwich may be smaller or more expensive than the ones they ate back East, but it’s tastier, healthier and easier on the conscience.

But the restaurant staff also meets resistance, sometimes even hostility: One customer vowed never to return after seeing that gefilte fish was off the menu because it was out of season; another complained loudly when chilled borscht wasn’t an option in November.

Now, Mr. Levitt and Ms. Adelman say they have reached a crossroads — there is more they would like to do to the menu, yet they fear the backlash. That is what inspired Tuesday night’s event. They are bringing out the big culinary guns to put the future of their restaurant under the spotlight. Is the concept of the sustainable deli itself sustainable?

On the panel next Tuesday: Michael Pollan, a Saul’s lunchtime regular; Willow Rosenthal, the founder of City Slicker Farms; Gil Friend, the author of “The Truth about Green Business;” and Evan Kleiman, the Los Angeles chef and radio host.

Ms. Adelman says they are in effect seeking permission from their customers to continue tweaking what she describes as “an ossified menu.” Just as Jewish food has evolved over the centuries, those who run Saul’s are hoping customers will, for instance, rediscover traditional Sephardic-inspired dishes, which put vegetables, legumes and seafood at the center of the plate rather than meat.

“We want to bring our customers with us,” she said. “They’re our family, our heart.”

It’s a familiar story for David Sax, who wrote the recently published book“Save the Deli.” He has spoken at Saul’s.

“The deli customer is very opinionated, the feedback never stops — which is a blessing and a curse,” he said. “No one is more committed to a new approach to the deli than Karen and Peter. And their concept of taking deli food back to a time when food was respected is a good indicator of where delis could go from here.”

Mr. Pollan also supports the efforts at Saul’s.

“They are trying to do something very admirable, but it’s challenging,” he said. “Good meat costs considerably more than feed-lot meat, and it’s easier for a white-table establishment to absorb the costs of doing it right.”

As for Mr. Levitt, he admits he’s frustrated. “Alice Waters looked at the French menu and reinvented it,” he said. “Why can’t we do the same for the Jewish deli menu?”

—

SUNDAY ROUTINES: NOVELLA CARPENTER, New York Times

Photo: Josh Haner, New York Times.

Novella Carpenter is a writer, urban farmer and Dumpster diver. Her memoir, “Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer,” chronicles her life on her small homestead near downtown Oakland. Ms. Carpenter, who studied journalism under Michael Pollan at the University of California, Berkeley, also helps run a biodiesel station in Berkeley, where she teaches chicken and rabbit rearing classes. She is working on her second book. (Her words have been edited and condensed).

UP WITH THE CHICKENS I get up at 7:30 to feed the chickens who gather on my back stairs and make a racket. Then I milk my goat, Bebe, while listening to NPR. All the days seem about the same. I do not have a weekend-centric, T.G.I.F. lifestyle.

PICK-ME-UP I drink a very strong cup of Lapsang Souchong, a smoky black tea. I call it bacon tea. I’m sure I’ll end up getting cancer from drinking it: they make it by roasting tea leaves over burning pine. I drink it with honey from my bees and goat milk from Bebe. I eat later — some figs from the tree, or some tomatoes, maybe a big salad from the garden.

MANUAL LABORI do farm chores: milking, checking on the rabbits, collecting a few eggs from the chickens. They don’t lay as much as they used to. I need to cull them, but they are so old they are just not appetizing. Sometimes I’ll go to my office in Oakland and write. Sometimes I have a lot of farm work. The big chores are mucking out the goat yard, which can get really smelly. I’m often making something like cheese or sauerkraut, so I have to flip the cheese or change the brine water for any olives I’m curing.

EXPEDITIONS Bill, my partner, and I might plan a seasonal activity like olive picking in Davis, strawberry picking or tomato harvesting. Or we might go sailing or just have a picnic on Bill’s totally grubby boat. It’s a 21-foot sailboat that one of his customers gave him. It’s fun to sit on while the sun goes down.

DIVING FOR DINNER At night, Bill and I will often go into San Francisco to see a movie at the Red Vic or eat at our favorite Indian place, Shalimar in the Tenderloin. The real reason for going to San Francisco, though, is Rainbow Grocery. Sometimes we shop there, but mostly we wait until the store closes and the Dumpster comes out. We’re mostly there for the animals: the goats love the cabbage leaves, the bunnies love the bruised apples and fennel stalks. But we often find stuff for us to eat, too, like yogurt or bananas. Rainbow is great because they put the good, edible stuff in boxes within the Dumpster, so it’s easy to find and doesn’t get dirty.

A BOOK AND BED I go to bed around 11 or 12. I usually read in bed until I fall asleep.

—

VISTAS: WALTER HOOD – A BEACH WITH A DIFFERENT VIEW, New York Times

Photo: Heidi Schumann for the New York Times

Walter Hood checks the tidal charts and heads to Crown Memorial State Beach on the island of Alameda at least once a week to run on the sand and take in the sweep of San Francisco Bay from a little-known vantage. Mr. Hood, whose landscape architecture firm designed the grounds of the de Young Museum in San Francisco, lives in Oakland, and he spends a lot of time traveling. In August, he accepted a Cooper Hewitt National Design Award at the White House. (His words have been edited and condensed.)

SENSE OF PLACE Sometimes you forget you live on the ocean. This beach, with its views of the water, mountains and cityscapes, is the closest place to home where I can get a profound understanding of the bay and where I live.

ECHOES OF THE EAST I grew up in North Carolina, and there’s an East Coast flavor to the promenade and the way the garden apartments and “Leave It to Beaver”-style homes here are built right on the water.

LOCAL HAUNT During the week, I can be the only person running on the beach, and it’s so silent. There might just be a few people long-boarding or practicing tai chi. Families come here on the weekends, but it’s never crowded like Ocean Beach. It’s low-key and it’s predominantly locals, not tourists. It reminds me how diverse the Bay Area is — with Latinos, African-Americans, Asians and whites. I remember that this is why I live here.

MESS IT UP Alameda Beach is one of the messy landscapes I like to talk about: it’s not manicured or overly designed. All the layers — the 1970s buildings, the marshes, the driftwood and the old-fashioned signs — are part of an everyday phenomenon. It’s not trying to be something it isn’t.

CITY-CENTRIC This is one of the few places where the view is not dominated by San Francisco’s crown: its skyscrapers and hills. The perspective is South San Francisco, Hunters Point and even, on a good day, the Pac Bell Stadium. Oakland, which I sometimes think has an inferiority complex, is there, too. It’s good to remember that the bay is one continuous place.